Strategy is often at the top of the agenda of CEOs and board members across the business community. Strategy is often seen as a lever to improve the competitiveness of the company and, ultimately, the return of shareholders’ investments in the enterprise. However, based on our experiences, despite attention from the board, the CEO and executive management, strategy often fails to deliver on its promises. We believe the link between strategy and its impact on bottom line results should be clear and direct, yet few are able to demonstrate this. This often causes significant frustration and, in some cases, even leads executive management to conclude that the concept of strategy is bogus.

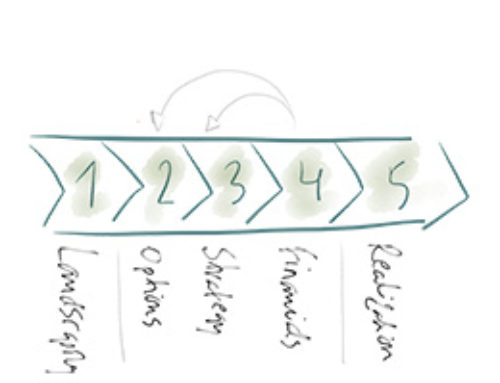

We strongly believe that thoroughly thinking through and realizing a strategy is instrumental for every company. Through our practice, we have had the opportunity to observe strategy efforts in many different companies representing several different industries. There are typically five issues that seem to constantly reoccur and these may explain what causes a strategy to fail.

1. Strategy context as strategy

1. Strategy context as strategy

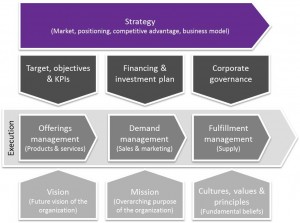

The first issue relates back to the actual definition of strategy and the awareness of the complex context in which it must exist. With an ambiguous definition of the actual strategy concept, it is common to focus on any of the components of the corporate context and call that the strategy.

Strategy mixed up with the targets, objectives & KPIs

Companies sometimes confuse their strategy with their targets, objectives & KPIs. For example:

Our strategy is to maintain five percent market share of business travellers on international flights

That is a target, not a strategy. The strategy should tell you exactly why five percent of the business travellers should chose to use this company rather than a competitor’s flights; for example, do they plan to compete with price, service, quality, etc.?

Other commonly observed examples include:

- “Our strategy is to globalize …” – This might be a good objective, but it is not a strategy.

- “Our strategy is to deliver attractive shareholder returns to our shareholders …” – This is pretty much a given objective in any commercially driven company and it is certainly not a strategy.

- “Our strategy is to outgrow competition …” – Yet again, this is a good objective, the strategy should say how to do that.

- “Our strategy is to increase revenue and reduce cost …” – This is the fundamental equation behind profitability, and although it might be a good objective, again it is not a strategy.

Strategy mixed up with the financing and investment plan

Companies sometimes have a tendency to confuse their strategy with their financing and investment plan. For instance, a company may claim that, “Our strategy is to invest to acquire and integrate key selected suppliers”. This may be a significant portion of that company’s investment plan but it is not its strategy. The company’s strategy needs to answer why it wants to acquire its suppliers. It might be to gain scale advantages, acquire core technology or mitigate the threat of new entrants. Only the strategy can explain the reason.

Strategy confused with the vision, mission or with cultures, values and principles

Executive management teams sometimes have difficulty articulating exactly the role of vision, mission, cultures, values and principles and these are often mixed up with the strategy.

Executive management teams sometimes have difficulty articulating exactly the role of vision, mission, cultures, values and principles and these are often mixed up with the strategy.

Our strategy is to become the number-one natural choice of retail bank for both consumers as well as for companies.

This is an ambitious vision for this bank. This statement cannot reflect its strategy, which must define exactly how the bank is going to become the number-one choice; for example, by offering the lowest interests on property loans, by offering the highest interest rates on savings account, by having the most developed retail network, best service, etc. The number of alternative strategies that could be used to realize the bank’s visions in this example is endless. However, failing to define a good strategy will definitely not improve the likelihood of becoming the number-one choice.

Strategy mixed up with offering-, demand- or fulfillment-management

Offering-, demand- and fulfillment-management are all very important components of the corporate context. However, we sometimes see examples when these are mixed up with the strategy of the company.

“Our strategy is to sell our ERP solution by teaming up with the leading System Integrators as channel partners.”

The above statement could be an important part of the demand- and fulfillment-management plan, since it articulates the company’s intention to sell and deliver its ERP solution through a partner network rather than through its own salespeople and engineers. However, it does not represent the company’s strategy, unless of course the distribution model is what makes the company unique. The above statement does not clarify why the end-users should buy this company’s ERP solution rather than that of one of its competitors. This is something that the strategy should tell us – does it have a lower total cost of ownership? Does it have unique functionality? Is it better integrated with other existing systems?

2. Strategy as functional plans

2. Strategy as functional plans

One of the most common pitfall is to confuse the company’s strategy with its functional plans. This is what typically happens when you hear the CEO, executive management and colleagues talking about the HR strategy, the supply chain strategy, the marketing strategy, the sales strategy, the product strategy, the R&D strategy, the recruitment strategy, the distribution strategy, the sourcing strategy, etc. The word ‘strategy’ can be put after just about any function in a company. Hopefully by now, you understand that we are actually talking about the functional plans, not the strategy of the company.

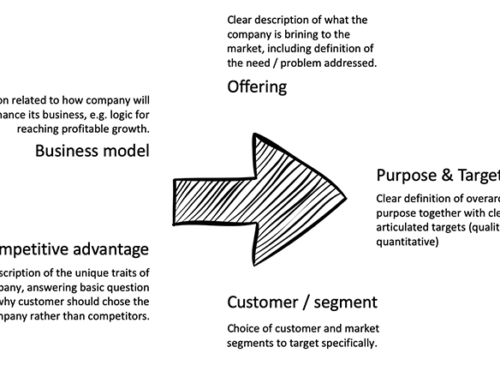

A company can only have one strategy – the corporate strategy that defines the market in which the company should play in, how it should earn its money and how it should compete in that market. Once the strategy has been clearly articulated, it is necessary to define functional plans that support the overall strategy.

3. The future-centric strategy

3. The future-centric strategy

For some reason, people tend to get somewhat futuristic when they start thinking about strategy; they see the strategy as a resolution for the future. This is another common pitfall.

Essentially, the strategy should define what market to play in, what position to take, how to compete and how to earn money. Furthermore, the strategy should be valid here and now; no company can earn more money today by defining how to compete in five years. However, no strategy, regardless of how good it is, will last forever. Ultimately, the sustainability of your strategy will come down to how easy it is for your competitors or by new players entering the market to imitate it. It will also come down to the dynamics of your industry.

4. Bottom-up strategic planning

4. Bottom-up strategic planning

The process for developing a strategy has been widely discussed and debated in the business community for a long time. There are clearly different theories and opinions as to how to best develop a good strategy. Strategic planning is an interesting theme, which is worth exploring in more detail in a separate article. However, having had the opportunity to review several companies strategy development processes, we are convinced that this is also one of the most common reasons why companies fail to reach a good strategy.

In some cases, executive management has come to the conclusion that the strategy development process need to be inclusive enough to engage functional heads and/or middle-management in the organization. There is nothing wrong with the intention; in fact, it is the opposite because the deep knowledge about the business apparently remains distributed in the organization.

The problem arises when the CEO and his or her management team decide to start the strategy process from a functional or middle-management level without giving any clear upfront direction. What typically happens is that functional heads and middle-managers start working with the strategy assignment fully energized and fully engaged, happy to finally be at core of the company’s strategy process. The functional heads and middle-managers will, in-line with the approach from the CEO, also involve department heads and key staff to get commitment to the strategy. After three months of hard work, the functional heads and middle-managers submit their strategy to the CEO’s office according to the original process timeline. When the CEO finally reads all of the strategies contributed from his or her functional heads and middle-managers, he or she will immediately realize that they will not add up. We have never observed a company that runs a distributed bottom-up strategy process and ends up with 10 strategies that are in perfect harmony with one another. What happens is that head of sales suggests investing in the sales-force with the argument that customer intimacy is the key differentiator. Meanwhile, the head of manufacturing wants to invest in a large manufacturing unit in a low-cost country, since he is convinced that the business is all about cost. The head of R&D is convinced that the only way to compete is through superior technology and suggests investing further in the R&D organization and opening up a new site in San Francisco.

The problem arises when the CEO and his or her management team decide to start the strategy process from a functional or middle-management level without giving any clear upfront direction. What typically happens is that functional heads and middle-managers start working with the strategy assignment fully energized and fully engaged, happy to finally be at core of the company’s strategy process. The functional heads and middle-managers will, in-line with the approach from the CEO, also involve department heads and key staff to get commitment to the strategy. After three months of hard work, the functional heads and middle-managers submit their strategy to the CEO’s office according to the original process timeline. When the CEO finally reads all of the strategies contributed from his or her functional heads and middle-managers, he or she will immediately realize that they will not add up. We have never observed a company that runs a distributed bottom-up strategy process and ends up with 10 strategies that are in perfect harmony with one another. What happens is that head of sales suggests investing in the sales-force with the argument that customer intimacy is the key differentiator. Meanwhile, the head of manufacturing wants to invest in a large manufacturing unit in a low-cost country, since he is convinced that the business is all about cost. The head of R&D is convinced that the only way to compete is through superior technology and suggests investing further in the R&D organization and opening up a new site in San Francisco.

The CEO will never be able to pull together a comprehensive corporate strategy based on the contributions from the organization and whatever strategy he or she chooses, a large part of the organization will be disappointed with the decision, given that they had to give up there found belief about the company’s strategy.

The worst-case scenario, and unfortunately the most likely outcome, is that the company that chooses a truly bottom-up approach ends up having no strategy at all or perhaps a very weak strategy as a result of having had to make so many compromises.

5. Missing the big opportunities

5. Missing the big opportunities

One of the most appealing aspects of strategy is that it sometimes allows you to reinvent your own business, and sometimes even a whole industry. In most cases, however, this requires you to realize and break the current paradigms under which you currently operate. Realizing that your thinking is stuck in a specific paradigm can be hard. Breaking that paradigm is even harder. This is why one of the most common strategy pitfalls is related to missing the big opportunity, the opportunity that requires you to fundamentally rethink how you do business.

If you are in the business of selling cars, your competitive paradigm is most likely geared towards thinking about competition through the quality and the features of the car, your brand and/or the cost of the car. Recognizing that you are thinking within that paradigm will also allow you to break that paradigm, at which point you can start to think about other means of competing. For instance, rather than selling a car for 20,000 Euro, can you sell a year’s use of that car for 5000 Euro? After five years, that car will have earned you 25,000 Euro and you will still own it. Of course, a new business model like this requires thorough research and lots of thinking, but if you had stayed in your old paradigm you would never ever have come up with the idea in the first place.

If you are in the business of selling cars, your competitive paradigm is most likely geared towards thinking about competition through the quality and the features of the car, your brand and/or the cost of the car. Recognizing that you are thinking within that paradigm will also allow you to break that paradigm, at which point you can start to think about other means of competing. For instance, rather than selling a car for 20,000 Euro, can you sell a year’s use of that car for 5000 Euro? After five years, that car will have earned you 25,000 Euro and you will still own it. Of course, a new business model like this requires thorough research and lots of thinking, but if you had stayed in your old paradigm you would never ever have come up with the idea in the first place.

Avoiding strategy pitfalls increases the likelihood of success

Many companies find themselves failing to develop a good strategy that allows them to remain competitive in the market and prosper through profitable growth. There are many pitfalls to blame for that, definitely more than the five that have been explored in this article. Learning to recognize the strategy pitfalls will help you avoid them and, ultimately, also increase the likelihood of success.

Before engaging in another strategy development process, make sure you invest the time upfront and think through the pitfalls you experienced in previous process. That is, of course, if you are not one of the few unique individuals in this world who has not experienced any of the strategy pitfalls!

About insight on strategy

Strategy is one of the most overused and misused words in the business community. It is a term that everybody loves to use but few dare to explain. 2by2 publishes Insights “On Strategy” to help companies improve their ability to create value through strategy by better understanding what strategy actually is, by learning how to spot the difference between a good strategy and a not-so-good strategy, and by gaining perspectives on the most common pitfalls when developing a strategy.

Previously published articles in this series:

- A definition: http://www.2by2.se/insight-on-strategy-a-definition/

- Competitive advantage: http://www.2by2.se/insight-on-strategy-competitive-advantage/

- Strategy context: http://www.2by2.se/insight-on-strategy-the-strategy-context/

- The good strategy: http://www.2by2.se/insight-on-strategy-the-good-strategy/

[…] Strategy pitfalls: http://www.2by2.se/insight-on-strategy-strategy-pitfalls/ […]

[…] The good strategy: http://www.2by2.se/insight-on-strategy-the-good-strategy/ Strategy pitfalls: http://www.2by2.se/insight-on-strategy-strategy-pitfalls/ The strategy development process: […]

[…] […]